I used the phrase “holy, canonical, Scripture” in a conversation yesterday. This is a phrase I learned from reading David H. Kelsey’s book, Eccentric Existence: A Theological Anthropology, vol. 1 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2009), as well as most of volume 2. I was invited by my beloved Fuller Seminary professor (and form whom I was a teaching assistant), Charlie Scalise, to read these books together—one chapter a month. This was one of the greatest gifts of my life, as we met in a coffee shop and unpacked this theology with Charlie’s guidance over a couple of years. The time did include theological discussions on the challenging book but also professional guidance as a new faculty member at Trinity Lutheran College, as well as pastoral care. These were months of conversations that were before, during, and after Eric’s death. I will be forever grateful for the mentoring over these years. I am also grateful for the deeper understanding of “holy, canonical, Scripture.”

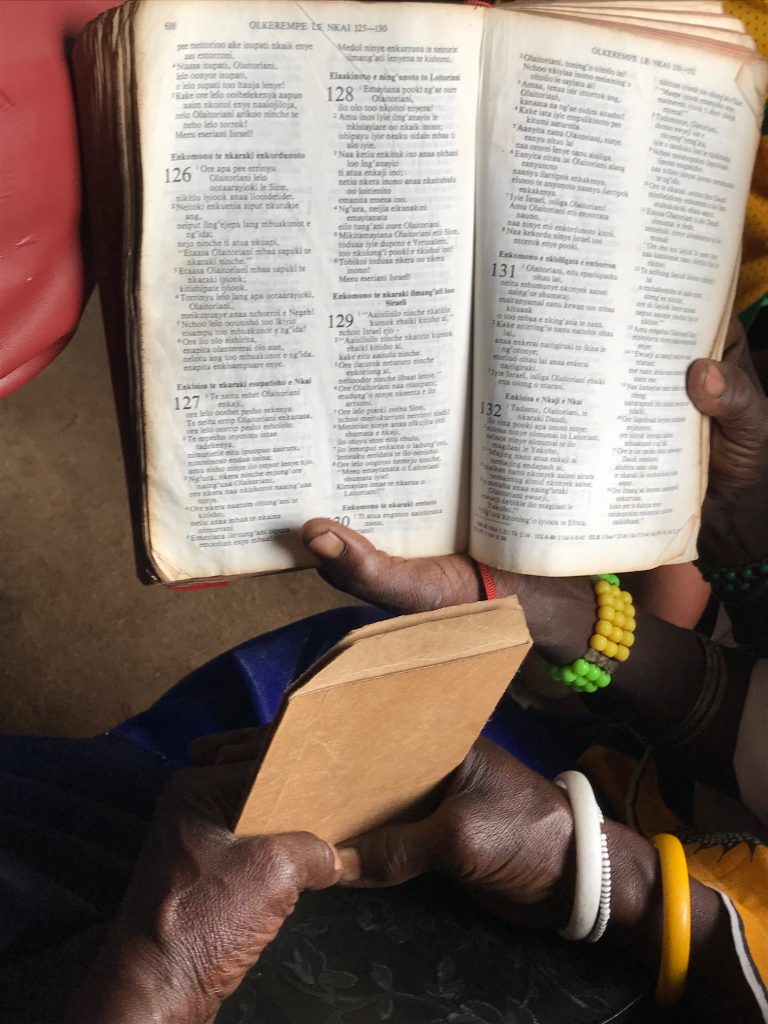

Women reading the Psalms in Maa in the Kimaasai Bible, Biblia Sinyati, at Irbiling Lutheran Church.

Yesterday, I was in a Zoom meeting with my research team at VID Specialized University, in a conversation to shape a research proposal to submit to the Norwegian Research Council (NFR in Norwegian). Three other biblical studies colleagues—including Knut, my “doctor father”—started these conversations over 2 years ago, as we all work really well together. The other 2, besides Knut, are my hiking buddies when I’m in Norway. However, the challenge we realized is that the project needs to be multi-disciplinary, and the NFR does not consider both Old Testament and New Testament scholars as multi-disciplinary! So, we are expanding our scope and the target area of research to be beyond a Maasai project but also to include the Sámi people group—the indigenous people of northern Scandinavia. This makes sense for a Norwegian funded project. Both the Maasai and Sámi are pastoralists, both have had histories of colonialist oppression, and both are still dealing with government policies that are oppressive. In addition, there are Christian traditions and inculturated interpretations in both contexts. This is interesting for us biblical interpretation geeks!

Our research approach is to recognize that religion sometimes had a negative role supporting colonialism and oppressive treatments—not always, but all too often. So, religion and corrective biblical interpretations can be part of the restoration of Shalom—which includes justice, and we think that the NFR could consider this approach favorably. The foci of our research are: 1), the Bible, 2) Indigenous people groups (Sámi and Maasai), and 3) sustainability hermeneutics (hermeneutics simplified is the philosophy of interpretation).

So, we’ve added a very brilliant Sámi researcher (with a PhD), who is an expert on the Sámi traditional religion, Christianity in Sámi contexts, and the role of the Church of Norway that was complicit in colonization and oppression.

The Zoom meeting included a discussion on what is “Bible.” Is it just the Hebrew and Greek texts of the Christian Bible? Does it include how people interpret the Bible in various contexts? Does it include the intersection of how the Christian teachings get interpreted through the traditional Indigenous stories? I actually have written an article comparing the Jacob and Esau story in Genesis 27 with a Maasai legend that has distinctive similarities (yet, I’ll come back to this in wrestling with “holy, canonical, Scripture”). Forthcoming publication: “Twin Stories of Brothers: A Comparative Analysis of Jacob and Esau with the Maasai Legend of Senteu and Olonana” in Religion och bibel, the Nathan Söderblom Sällskapet (Society) journal, Uppsala, SWEDEN, spring 2024.

So, does “Bible” have to be written? Does it include sacred oral stories from Indigenous peoples? If so, how do we understand “sacred?” Which stories are sacred, and how do we know this?

I then brought “holy, canonical, Scripture” into the conversation. I said that I, as a researcher, have a broad hermeneutic that eagerly engages various perspectives, and the theorizing upon this is question is an important part of research, and yet, as a biblical scholar and person of faith, I want to make sure that “holy, canonical, Scripture” remains a valid conversation partner in our research.

Not so elegantly, I added that if there is not a place for “holy, canonical, Scripture” as a dialogue partner in this research, then I don’t see a place for me in this research, as it is not in alignment with my calling. I really don’t like this sense of what can be seen as a threat, such that I will drop out if X doesn’t happen, but I was clear that I really do endorse the scholarly conversation and theorizing that is diverse. And still, I understand that my calling is such that my scholarship is to be in service to the church—not just for my professional development, getting fancy grants, getting published, etc. If we diluted or lost the perspective that Christian Scriptures are revelations from YHWH and authoritative for life and faith (yes, the interpretation of these issues remains HUGE, but that I why I am a biblical scholar!), then I would not see a project worth investing my time in.

One colleague added that there is an article she read stating, “If everything is sustainability, then nothing is sustainability.” So, similarly, if everything is Bible, then nothing is Bible. Another noted, for those of us who are biblical scholars, we are experts in exegeting the ancient Hebrew and Greek texts in their ancient contexts (and analyzing historical and contemporary interpretations), and we are not experts in analyzing oral literature of other people groups. This indicates that if that if the understanding of “What is Bible?” gets really broad, then for us biblical scholars, we actually lose our competence.

In this conversation, I am grateful for my year at Wartburg Theological Seminary and colleagues there who made it clear that the gospel of Jesus Christ is central. Yet, good and very important aspects—like social justice and environmentalism—masquerade as gospel, which is then a false gospel. My colleague at Wartburg, Samantha “Sam” Gilmore, teaches homiletics. She made it plain for evaluating a sermon by asking, “Did Jesus have to die for this sermon?”

I truly value the oral literature of the Maasai, and I cherish innovative ways to link the gospel of Jesus Christ to a different culture, as Paul did in his speech on the Areopagus (Acts 17:22-23), but Jesus didn’t have to die for the truths within the oral literature of the Maasai. That is the crux (pun intended) of “holy, canonical, Scripture,” it reveals the God of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Many other sources can point to this, but they are not divine revelations that bring us to Jesus Christ.

An “authentic” African Christianity?!?

Tangential but related to the crux of this conversation is a paper I reviewed this week. It was submitted to a journal, and I was asked to be one of the “blind” (anonymous) reviewers. In the paper, the African author stated, “We need to develop an authentic African Christianity.” I believe this is impossible. Now, I am one who has focused my professional calling on inculturated interpretations of the Bible in Africa, so I’m passionate about legitimate, valid, and plausible (these are all technical terms, let me know if you’d like to know more) contextual interpretations of Scripture and manifold expressions of Christianity around the world. So, why do I think that an “authentic” African Christianity is impossible.

First, there are over 3,000 people groups in Africa. So, which context will determine what is “authentic” for the other 3,000 people groups on the continent? The one cultural expression that wins would then have a colonial-like domination (a “power over” form of colonizing the mind or African church).

Second, and more critically, the revealed holy, canonical, Scriptures are written in ancient Hebrew and classical Koine Greek. So, every expression of Christianity is intercultural. Yes, there are legitimate, valid, and plausible expressions of Christianity in every context and even every language! (See Lamin Sanneh, Translating the Message.) However, Christianity will never be an authentically American, African, Norwegian, Peruvian Christianity. Even for Palestinian Christians in the Levant—who are probably the closest candidates for authenticity with a direct lineage to the early church—there are 2,000 years of cultural changes and a spoken language that is different than the Scriptures. Christianity will always be intercultural in every context.

Finally, Christianity must always provide a critique of a culture. Note that I’ve already affirmed that every culture is a vehicle for inculturating the gospel, so I’m not denigrating culture as a whole. (See Stephen Bevans, Models of Contextual Theology.”) However, there is no culture so pure that it does not stand without a need for transformation by the Holy Spirit, because cultures are products of humans with an inherently sinful nature. So, if it becomes “authentically” African (or American or Brazilian or São Tomé and Príncipian), then that form of Christianity has diminished its power to be transformed by the Holy Spirit in order to be more in alignment with God’s creation and prophetic ideals—which are transcultural.

Yes, this is what a biblical interpretation does on a beautiful Saturday—after finishing doing my laundry by hand—which gave me a great opportunity to ponder these issues.

Mungu akubariki! (God bless you! in Kiswahili)

Mikitamayana Engai! (God bless you! in Maa)