My research sites are predominantly in places where I am known and trusted, because relationships are vital. It is false to think that one can be a neutral unbiased researcher for many reasons (no one is neutral and hermeneutical philosopher, Hans-Georg Gadamer, say that our non-neutral interests motivate us to ask questions, but I won’t bore you with this right now). In addition, without a relationship, there would be a natural protective response by the research participants, especially when a white person (mzungu) comes and asks questions in a Western mode (a paper survey). Now there is another risk on the other side of the pendulum swing, that the research participants will subconsciously reply with information that they think I want to hear. So, each survey introduction has a statement to indicate that the best response—what I would like to know—is your perspective or opinion.

However, there is another challenge; paper surveys are very difficult for women who have never had the opportunity to go to school and do not read or write. Many researchers (and early anthropologists) would stick to getting information from those who are literate and speak the lingua franca of this country, Kiswahili, which means that until the last decade or two, the research participants would be men. However, I am committed to the struggle to find ways to include Maasai women’s voices. With the help of Bethany, the long-term ELCA missionary (who is the facilitator of the Naapok Women’s Cooperative), we figured out a plan for the pre-lesson survey that would be respectful and culturally sensitive. We could not do paper surveys for women who do not even sign their name with a pen, but rather, they make a thumb print. The plan Bethany and I developed was for one of my stakeholders, Julius, is from Ketumbeine (a referral from Bethany) would orally present the questions and discuss the question as a group. Their whole community and work as a cooperative is done as a group. Julius is trusted, as he helped the women develop their constitution. So, Julius went prior to the day of lessons and met with the Naapok women for 2 hours and then wrote up a report.

It sounds like there was some discussion about the terminology that was new to them. (Yes, I’ve worked with my stakeholders to develop climate science terminology that would be consistent for the 3 different writers in 2 languages (Kiswahili and Maa). So, this protocol is different from what was done for the other groups who had at least primary school and could read and write. With the appropriate explanations of the divergent process, I see that the greater good is that the lessons are taught in a way that the women can be informed and create the space for them to discuss the concepts.

Unfortunately, Suzana (the writer of the lessons) was sent with short notice to the capital for an important meeting for her primary job. For the sake of calendars, Bethany and I decided to call upon Julius again. His master’s degree is in geography and environmental management, and he has professional experience with environmental NGOs (in addition to being a great guy—and tri-lingual with English, Kisawhili, and Maa). So, I left my house early, picked up Julius along the way, and arrived in Ketumbeine for a lovely day with the Naapok women.

The lessons are developed to engage active learners with good opportunities for small group discussions and reporting. We made sure there was one who could read and write in each group.

While there is too much to relay from the day, here are three important developments.

First, in working with developing the lessons with Suzana, we realized that “the greenhouse effect” was actually a distraction from the content as these people have never seen a greenhouse. So, it would take a huge effort to explain a greenhouse to then abstract it in the metaphor. Thus, we’ve been using the “blanket effect.” The Maasai are known for their blankets, and my flipchart picture has a Maasai blanket keeping in the “planet warming gases.” Julius, a good Maasai, had his Maasai blanket which was used for a visual demonstration! Of course, I got a picture!

Second, one woman asked, “Why should we be concerned about taking care of the environment, because the government is just going to take away our land.” Oh, this makes my heart ache for the Maasai. Yes, the government is eager to take Maasai land through weaponizing conservation as a ruse to increase tourism revenues, especially lucrative hunting safaris. (See McCrummen, Stephanie. “‘This Will Finish Us:’ How Gulf Princes, the Safari Industry, and Conservation Groups Are Displacing the Maasai from the Last of Their Serengeti Homeland.” The Atlantic, 8 April 2024.)

Julius invited me to respond. I said (which was translated to Maa), “First, God has commissioned us to care for God’s creation. It is first God’s creation. Second, many Maasai are working together to protect traditional Maasai lands, and it is making a difference.” It became understood that the women are being left out of the conversations. The men are in seemingly endlessly talking about how to protect their lands and are in dialogue with the local leaders, but the information about the meetings and what is said is not being passed onto the women. So, Julius, who has been in some of the dialogues was able to bring in some of the information. How discouraging it must be to be marginalized within your own community due to the patriarchal structures. Traditionally, the men think of the women as being like children and not having the mental acuity to engage in the important discussions.

Thus, these lessons were not only important for the content of creation care in a Maasai context (integrating biblical creation care, traditional environmental knowledge, and climate science), but this day ended up equipping the women with information to be stronger participants in their own community and a bit of empowerment to be able to engage in the dialogues with the men on issues that have a huge effect upon their and their children’s lives.

Finally, at the end of the sessions, one of the women stood up—of her own initiative—and said that these lessons were very important. These lessons need to be shared farther with the other women and even with the men! Bethany turned to me, with the translation, and said then commented, “There could not be a better compliment than this!”

So, yes, it takes more effort to engage the women who were never given an opportunity to go to school, but as one of my students, Rebecca, at the MaaSae Girls Lutheran Secondary School taught me: “If you teach the mama, the whole family will learn!” Yes, the research protocol is messy for this group, but the greatest good is being a blessing to the women—not me trying to get clean research data. Bethany confirmed that this was a blessing for the women. Hallelujah!

P.S.: And it is pretty cool going to Ketumbeine, where we get to see elephants, giraffe, hyena, impala, etc.!

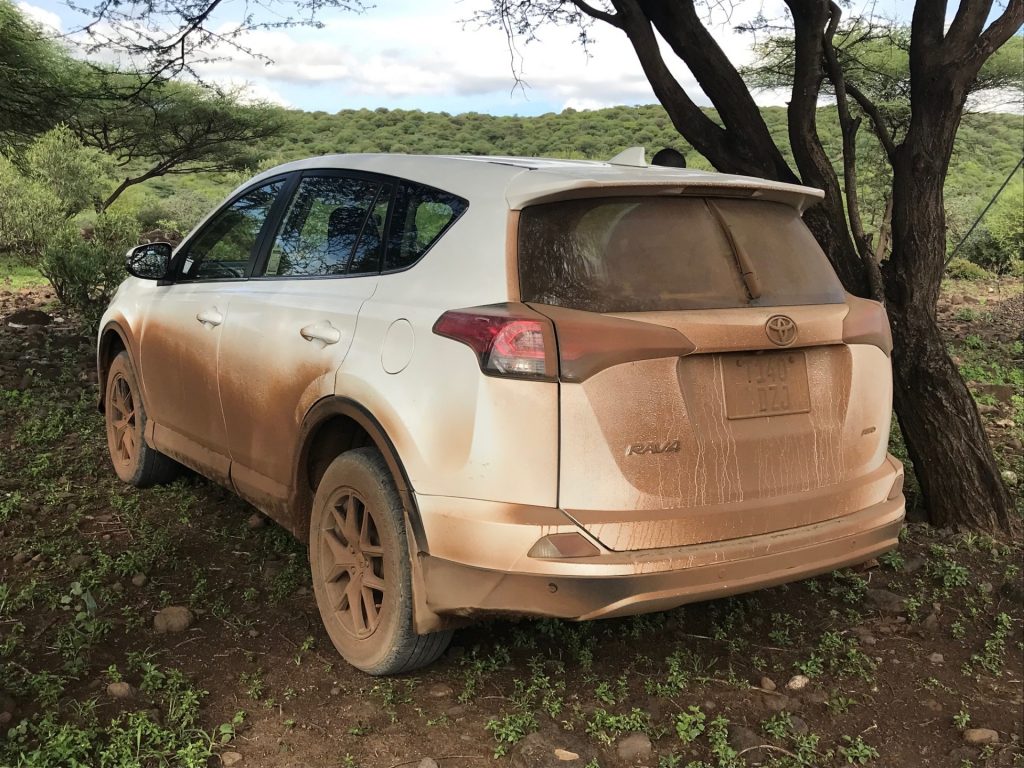

P.S.S: I paid for a car wash also with a rental of my friend car. Thanks Laurie!

Mikitamayana Engai! / Mungu akubariki! / God bless you!